[divide margin_top=”10″ margin_bottom=”10″ color=”#a0a0a0″]

Abstract

In the past online learning has often resulted in a re-creation of teachers’ normal, pedagogical practices (Cooney & Stephenson, 2001; Alexander & Boud; 2001). My interest in e-learning arose through personal experiences in providing ‘traditional’ (face-to-face) CPD for teachers over a number of years when I questioned the extent to which my provision had any lasting or deep impact on teachers’ thinking and practice. E-learning offered a new means of supporting teachers in CPD.

This study was conducted within a collaborative e-learning project. There is seldom agreement in what is meant by the word ‘collaboration’ (Dillenbourg, 1999) though in respect of this study not only were there collaborative discussions, some teachers joined the project with a colleague, allowing involvement of pairs to be evaluated. Additionally two of us collaborated as joint project leaders sharing the management of this project and co-facilitating discussions, although each of us focused on different aspects for research: this aspect of collaboration is not explored within the context of this study.

Totten et al and Gokhal argue that shared learning helps learners to be responsible for their own learning: through doing so they become critical thinkers, analysing, synthesising and evaluating concepts (Totten, Sills, Digby & Russ, 1991; Gokhale 1995).

The context for discussion focused on an innovative and extensive, evidence-based research study we had conducted, into children’s mathematical graphics (3 – 8 years) (Worthington & Carruthers, 2003). The online forum allowed teachers to develop their understanding about this aspect of children’s development and pedagogy whilst simultaneously developing their own practice. This would allow e-learning to be embedded, an aspect emphasised in the government’s e-learning consultation document (DfES, 2003a).

Teachers elected to participate in this online community of practice, an additional and significant factor which may also have contributed to its success (unexplored in the context of this study). Many teachers explained their interest in the content of the online discussions as a specific reason for choosing to participate. It is also important to note that teachers recruited for this project were committed, enthusiastic and generally highly motivated: most also teach in Early Excellence Centres.

The literature critique explores aspects of dialogue, context and technologies through a focus on the work of Bakhtin; Mercer; Kress and Nardi and Day. These are significant themes and provide a context for the forum explored within this study. The findings indicate that the dialogical context can be enriched with the use of e-graphics when they are contributed by the participants in the forum and are sourced from the children in participants’ own classrooms.

This study therefore may be said to be a search for what Habermas defines as an ‘ideal speech situation’ in which dialogue is unfettered and free of distortion (Habermas, 1984). The extent to which an ‘ideal speech situation’ has been achieved points to an ‘information ecology’ (Nardi & Day, 1999) supporting positive outcomes for teachers’ professional development. Analysis of the dialogue through ‘cohesive ties’ techniques (Stokoe, 1996), highlights rich language use and collaborative meaning-making. Analysis of transcripts of telephone interviews emphasises the extent of teachers’ meta-cognitive concerns and is a significant indicator of deepening levels of learning through this means of CPD. Woven through the study, questions concerning teachers’ views about joining the project in pairs (with a colleague) led to a number positive outcomes. There are also indicators of impact on teachers’ own practice during the short duration of the project (summer term 2003) which extended to some other colleagues: these findings suggest significant benefits for teachers who are involved in CPD through e-learning. As a consequence of their involvement, the Early Years teachers in this project also reported increased confidence and enthusiasm about their own use of ICT.

Author: Maulfry Worthington

Publication Date: 2004

[s2If !is_user_logged_in()]More… To see the complete Case Study, please Login or Join.[/s2If]

[divide margin_top=”10″ margin_bottom=”10″ color=”#a0a0a0″] [s2If is_user_logged_in()]Introduction: the efacilitation context

For the purposes of this study I have the term ‘collaboration’ to refer to:

- Teachers learning through shared discussion within the on-line community of practice

- Teachers collaborating in pairs.

I aim to treat the collaboration of pairs as a distinct issue although clearly there is some overlapping when the two aspects coincide.

Discussions took place through an online forum ‘MirandaNet Web Graphics Discussion’. A significant feature of is the use of an innovative feature whereby examples of children’s work (children’s original mathematical graphics and photographs of children working) are visible on the screen at the same time as the discussion threads. The concept for this feature was ours but developed through the technical expertise of MirandaNet’s web manager. Of major importance is the fact that examples of children’s work are from the teachers’ own classes, either emailed after scanning; as digital photographs, or posted to us. These examples appear on the left of the screen on the same page as the forum, as a moving slideshow. Members of the online community are also able to click on any of these ‘thumbnails’ to enlarge them.

Through their involvement teachers would also be developing their skills in ICT. Recent research into early learning shows that ‘significant ICT training at a personal level is needed for many early years practitioners’ (Moyles et al p.136, 7.51). Teachers’ low level of use and initial anxieties about ICT in this study, whilst not a focus, are in marked contrast to the findings of a study by PARN (2001) which revealed a high level of internet use amongst professionals (2001, p.2). This present study may also make a small contribution to the government’s targets in the ‘5 action areas’ (DfES, 2003b).

Cohort:

We recruited a cohort of 18 teachers, most of who teach in Early Excellence Centres throughout England, from Cumbria to the Isle of Wight:

83% teach in under-fives settings

11% teach in mainstream settings (Reception and R/Y1)

6% teach in special education (Reception)

Of these, 8 joined in pairs and 10 as individuals.

Teachers elected to participate in this online community of practice: we believe this may be an additional and significant factor in ensuring its success (unexplored in the context of this study). At the onset of the project many teachers explained their interest in the content of the online discussions as a specific reason for participating. It is also important to note that most teachers recruited for this project were committed, enthusiastic and generally highly motivated: most also teach in Early Excellence Centres

Literature Critique

A central theme of this study is dialogue and the way in which it supports learning. One of Bakhtin’s significant legacies is his perspective on ‘utterances’ reflecting the speech of others through ‘ventriloquation’ (Bakhtin, 1981; Holquist, 1981) or ‘multivoicedness’ (Wertsch, 1991).

‘The word in language is half someone else’s. It becomes “one’s own” only when

the speaker populates it with his own intentions, his own accent, when he

appropriates the word, adapting it to his own semantic and expressive intention.

(Bakhtin, 1981. pp 293-294).

The writings of Bakhtin and Volosinov – both contempories of Vygotsky – are often referred to when using the term ‘dialogical’. In their views language originates ‘in social interactions and struggle’ (Maybin. (2003. p.64). Volosinov viewed meaning as ‘realised only in the process of active, responsive understanding’ between speakers, (1929/86. p.102-3). This dialogic process, Wegerif argues, can lead to ‘effective collaborative learning’ (2001. p.11).

The examples of young children’s ‘written’ mathematics (as e-graphics) in this present study also have a pre-history – of others’ marks and written methods – and are therefore polyadic. Each representation encapsulates themes, styles and thoughts of others, whose earlier representations – like our utterances – themselves embrace features of many others’ representations. Wells, (drawing on Freeman, 1995; Donald, 1991 & Wartofsky, 1979) argues that ‘because each advance in representing, the previous modes were not lost, we have a repertoire of modes to hand’ (2000. p.5).

This view is significant in the context of the collaborative context of online communities, and specifically in the context of this forum. Mercer argues that ‘language is often used in conjunction with these other meaning making tools’, (i.e. gesture and drawings) ‘which can be used to draw physical artefacts into the realm of the conversation’ (Mercer, 2000. p. 23). ‘Original’ creative acts, whether speech or drawings must therefore always be regarded as integrating the creative acts of others.

Since language is ‘not simply a system for transmitting information (but)… is a system for thinking collectively’ (Mercer, 2000), p. 15), CMC offers advantages when exploring ‘a particular complex issue’ (Mercer, 2000, p. 127). It is clear that CMC must therefore offer special advantages to the educational community with its diverse and complex issues of learning and teaching.

But online communities of practice are more than dialogue between participants: the fact that the dialogue is computer-mediated contributes to the rapidly changing landscape of language and literacy. In his 2003 study Kress’s approach to new literacies is challenging and thought-provoking, the affordances of the medium provide new opportunities. The role of e-facilitator is a very different role to that of ‘teacher’ or ‘lecturer’, forcing us to recognise the ways in which technology and new forms of media ‘will produce far-reaching shifts in relations of power’ (Kress, 2003, p.1). This is likely to be felt throughout education, not least in the context of CPD: the expert leaders as knowledge-giver have gone and in their places are efacilitators. As Mercer observes, ‘like any other medium, CMC will only be as good for collective thinking as its users make it’ (2000, p. 129).

Mercer suggests that ‘fluency in discourse is likely to be one of the obvious signs of membership’ (Mercer, 2000, p. 106 – 7). To what extent did we achieve fluency in our online discussion with teachers? The ‘cohesive ties’ analysis used in this current study (Stokoe, 1996, cited in Mercer, 2000), is, Mercer suggests, one way in which participants develop continuous lines of thought, amplifying development of shared meanings. In Bohm’s view (1996) dialogue is ‘a stream of meaning flowing among and through and between us’ (p.6). The relationship between Bakhtin’s ‘ventriloquation’ is clear and further emphasised in Wegerif’s work on a ‘dialogical model of reason’ which is in turn supported by Lipman’s philosophical ‘community of inquiry’ (1991). The listener’s role is implicit and active, requiring ‘thoughtful attention’ (Fiumara, 1990). Mercer’s introduction of the term ‘interthinking’ helps focus our attention on the collaborative, co-ordinated intellectual activity of language use, and its significance within the context of meaningful online dialogue.

Technologies, in particular the screen (television and computer) have now overcome the dominance of the book, leading, Kress argues, to ‘an inversion of semiotic power’ (p.9) in which the visual mode holds sway over the partial mode of writing: ‘as a consequence, writing in no longer a full carrier either of all the meaning’ (p. 21). Kress’s semiotic exploration explores not only images and text on and off screen but the use of space. ‘Reading’ of the e-graphics and text on our ‘MirandaNet Graphics Discussion’ forum must subconsciously take into account these complex layers of meaning-making, for ‘the world told is a different world to the world shown’ (Kress, 2003, p.1). The affordances of new technologies and the dominance of the screen will, Kress argues, ‘have many consequences’ (2003, p.166).

Nardi and Day (1999) use the term information ecology; describing ‘a system of people, practices, values and technologies in a particular local environment’ (p. 49). Rather than ‘communities of practice’ (Lave & Wenger, 1991) this term suggests something more compassionate; embracing different aspects of the social and technological that, the authors propose, ‘co-evolve’. Social practices, they argue, help shape the technologies and ultimately advocate ways to use and adapt them. In such ecologies technology need not intimidate or rule, but is reciprocal and interdependent. For Nardi and Day, there is ‘a powerful synergy between changing tools and practices. As people become more involved… they will be able to articulate more clearly and more precisely what works and what doesn’t, what they value and what they need and want’ (Nardi and Day, 1999. p. 75).

Teachers in this study came with limited experience and some anxieties of ICT although all reported increased confidence in their use of ICT during the project (though this was not a focus of this study). Nardi and Day use the film Metrolopolis as a powerful metaphor for working with new technology. The changing use of technologies that allow CPD through elearning, must also ensure a ‘new future in which the minds that plan and the hands that do the work do not live in separate worlds, but are mediated by the human heart’ (Nardi & Day, 1999. p. 11).

Case Study

- Data collection

I based my study on a model of grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) which enabled me to ‘think systematically, critically and intelligently’ (Pring, 1978: p. 244-5). Responses from teachers and analysis of transcripts also allowed me to prepare an ‘audit trail’ that established a chain of evidence (Schwandt and Halpern ,1988).

Data was collected through:

- transcripts of the discussions

- questionnaires (end-point)

- telephone interviews.

Transcripts of online discussions allowed analysis of the discussion and the number of posting from each teacher helped determine levels of involvement.

Questionnaires on socialization were sent by email and by surface mail. 55% of questionnaires were returned completed. Rather than rely on a limited number of questionnaires I eventually used these questions as a basis for telephone interviews. This allowed me to explore issues in some depth and provided validity through responses from interviews with all project teachers.

Telephone interviews: interviews lasted for approximately twenty minutes each. Responses were analysed for aspects of language and teachers’ experiences and perceptions of collaboration in pairs.

- Methodology: gathering a chain of evidence

Section A. Language for learning; language about learning

- Cohesive ties technique: I am interested in ways in which teachers collaborated through online discussions to create individual and shared meaning. In order to analyse transcripts I used ‘cohesive ties’ techniques, (Stokoe, 1996; cited in Mercer, 2000) allowing focus on a range of language techniques (Mercer, 2000, p. 59) and highlighting collaboration through discussion.

I chose to identify three, main cohesive ties within transcripts of the online discussions:

- Repetition of a word or phrase

- Substitution – when one word (or phrase) is substituted for another with a closely related meaning

- Exophoric reference. Use of e-graphics allowed for what linguists term exophoric reference or ‘linguistic pointing’. Mercer argues that this is an example ‘of the way in which talk is related to the physical environment’. (Mercer, 2000. p. 23). The combination of talk and e-graphics (visible examples of children’s work on-line) creates powerful contexts for meaning-making through two semiotic systems.

- I analysed the language teachers used during telephone interviews: replies were written down during the interview and then typed immediately in full. In response to the question “Has the project influenced your teaching?” I noted that three key language features occurred repeatedly:

- meta-cognitive – relating to thinking and understanding

- affective – relating to feelings or attitudes

- practical pedagogical issues referring to changes in teachers’ practice as a result of their new knowledge

Section B. Collaboration – pairs and individuals

Fullan argues that collaborative cultures are highly sophisticated and that ‘all successful change processes are carried out in collaboration’ (Fullan, 1991, p.349). In Salmon’s model of teaching and learning online, interactions become increasingly collaborative as participants moved into ‘stage 4 – knowledge construction’ (Salmon, 2002. p. 11).

Through analysis of telephone interviews I was able to compare teachers’ experiences and perceptions of being in a pair.

Participants in pairs were asked if they had liked the experience of being in a pair. Individuals were asked if, with hindsight, they would have liked to participate in the project with a colleague, or would like to in the future (yes/no answers).

Features noted by teachers were counted and comparisons made between the number of features noted by teachers in pairs and by individuals.

________________________________________________________________________

SECTION C: Impact on practice

Impact on teachers’ own practice

To explore the impact of the online discussions on teachers’ practice and to determine differences for pairs and individuals, I first compared numbers of postings made by pairs and individuals.

Next, using responses to the question “Has the project influenced your teaching in the longer term?” I rated them ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’ (level) according to teachers’ descriptions of changes in practice. I then compared each individual’s rating to their number of postings, allowed me to determine if there was a relationship between number of postings and reported changes in practice.

To assess the extent to which talk contributed to teachers’ growing understanding, I counted the number of incidents of words relating to talk in their answers. I then calculated their use of ‘talk’ words as a percentage of all comments and compared the incidence of these words for both groups.

.

Sharing new knowledge

I asked “Did you have an opportunity to discuss what you were doing with colleagues?” I anticipated some sharing of new knowledge with teachers’ colleagues with whom they worked closely (e.g. nursery nurses, family workers). I also asked: “Did your input / discussion with colleagues have an impact on their practice?

________________________________________________________________________

- Analysis

Section A: Language

- ‘Cohesive ties’ analysis.

The thread entitled ‘different styles of children’s learning’ featured twelve postings, including the summary (which I omitted for purposes of analysis). This discussion was particularly rich, with a high proportion of descriptive language.

Use of substitution was especially evident as teachers described young children communicating and expressing their thinking through different media, for example:

“sensory exploration”

“sensory experience”

“exploring”

“explorations with …”

“visual and sensual”

This use of substitution allowed linkage of terms and topics between different speakers that helped them construct shared meaning. Individual teachers also used substitution several times within one posting, giving prominence to certain concepts and appeared to help clarify their intended meaning.

Repetition featured, though to a lesser extent. This had the effect of emphasising the topic(s) of an individual’s posting and may have lead to clearer, shared understanding within the online community. Exophoric reference was used least in this discussion since the topic did not use a child’s example (e-graphics) as a contextual foundation for the discussion.

In contrast, a transcript that focussed on a child’s example (e-graphics) visible on the screen and entitled ‘Nikita’, included several exophoric references, including the words: “this”; “top left” and “Nikita’s picture”. Other threads that focus on a child’s work use a number of exophoric references. When the teachers were discussing a specific example as in ‘Nikita’, it clearly aided understanding to have the visual context available for reference.

The third transcript I analysed concerned ‘different styles of children’s learning’. Discussion of boys’ approaches (in thread ‘A’) had led to this new thread on ‘gender issues’ where the word ‘boys’ exceeded that of ‘girls’ in a ratio of 2:1 highlighting participants’ interest in boys’ mark-making: this demonstrated how a topic can be carried over from one thread to another. I was able to trace not only the use of repetition and substitution but also the way in which links between language in one thread linked with language within a related thread.

Since the content of the discussions concerned the same subject (children’s mathematical graphics) there was considerable repetition and substitution of language across threads. This linked internal topics in a complex web of understanding and indicates the extent to which teachers co-constructed meaning within the community.

- Analysis of language used

The range of language included examples of:

Meta-cognitive: when teachers used words and phrases such as:

“heightened my awareness”

“thinking more”

“Cleared things in my mind”

Affective behaviour:

“I value what they children do more now”

“I feel very committed”

“I was excited”

Practical pedagogical issues:

“I keep lots of samples”

“I’m quite into compiling and emailing attachments now”

“I’m more prepared to take what I know into schools and pre-schools and demonstrate good practice”

Every incidence of these key areas was counted in each teacher’s interview transcript.

Table 1: Analysis of language used

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Language category Percentage of total number of words used to describe

changes in thinking, feelings and pedagogy:

_____________________________________________________________________________________

| Meta-cognitive: | 53% |

| Affective: | 28% |

| Practical pedagogical: | 19% |

The high percentage of meta-cognitive language suggests that thinking (learning, knowing and understanding) was a significant feature of teachers’ participation. Affective language (moods, feelings and attitudes) were also important, although to a lesser degree. Whilst some practical issues relating to pedagogy occurred, they were far less prominent: pointing to learning through CPD that goes beyond short-term or superficial ‘ideas’.

Section B: socialization – pairs and individuals

1a. Experience / preference for being in a pair

“Was it helpful to you to be with a colleague from your setting, in the project?”

Pairs: all teachers in pairs responded in the affirmative.

Individuals: 90% responded in the affirmative: the one remaining teacher was unsure but positive about her individual experience.

Comments from teachers in pairs included:

“Just being able to have someone to discuss things with – (someone) who understood – was good”

“We talked a lot about what the children were doing”

“It gave us a chance to evaluate – two heads looking at it together are better – together we had more ideas”

We discussed what was online”

“Twice we went online together”

It may be that since teachers from the same setting have a shared history, reciprocal knowledge provides additional support. The last teacher’s comment (above) raises the question whether there might be value in encouraging pairs of teachers to log on together, although comments from several of the teachers in pairs about difficulties of meeting together may militate against this.

Individual teachers recognised similar benefits and one explained:

“I did try to ‘buddy’ with a colleague at work. I explained about it and we looked at some of the children’s work”

Another individual spoke wistfully of two teachers in a pair (in the project) who taught at a nearby setting:

“It would have been enormously helpful! We have a ‘sister’ centre nearby. The two teachers there sparked ideas off each other. I spoke to their deputy head and he was very enthusiastic about what they were doing!” (1)

The level of affirmative replies from pairs reflects high levels of satisfaction in participating in pairs. In the light of their experience in this community, individual teachers anticipated that there could be benefits to participating with a colleague.

1b. Experience / preference for being in a pair:

It is significant that no teachers listed negative aspects of being in a pair (either experienced or anticipated). Teachers in pairs made an average of 4.75 positive comments each, compared to individuals who made an average of only 1.4 comments (anticipated benefits).

The benefits (or for individuals – anticipated benefits) indicate high levels of satisfaction and expectation concerning the value of participating with a colleague. Teachers in pairs were clearly better placed to comment on a wider range of benefits than individuals.

SECTION C: Impact on practice

- Level of involvement: number of postings

The eighteen teachers made a total of 93 postings during the online project. The lowest number posted by an individual was 1 and the highest 19. Of these, individuals made an average of 6.8 postings whilst teachers in pairs made only 3.1. This may reflect the fact that teachers in pairs could also discuss issues with their project partner at work (offline)

- Level of impact: relationship between number of postings and impact on practice

Without exception, teachers with the greatest numbers of postings (between 10 and 19 postings each) were found to report high levels of success / impact on their teaching.

Teachers who had made 2 – 6 postings all achieved medium levels of success within their practice. The exception to this was a pair of teachers who had made 4 and 6 postings each, whom I had rated with ‘high’ levels of success / impact on their teaching. This included some collaborative work that had a considerable impact on colleagues’ and children’s understanding (see (1) above) and may be due to their personal interest and enthusiasm.

- Two teachers who had barely participated (1 posting each) reported almost no impact on their practice. This demonstrates a correlation between active involvement in the online community and impact on teachers’ understanding and pedagogy. Their low levels of involvement suggest that, in Wegerif’s terms, they ‘failed to cross a threshold into full participation in the collaborative learning’ (1998. p. 38).

- Level of impact: perceptions of the value of talking

Language used by teachers in pairs and individuals was similar.

For pairs, 61% of positive outcomes referred directly to talk and discussion: ‘talked about what was on-line and what we were doing’; ‘talked a lot’; ‘discussed the children’; ‘talked about the maths’; ‘bounced ideas off each other’; talked a lot about things and planned what we could do’. This suggests also that teachers in pairs had greater opportunities for face-to-face discussion about issues concerning the content and pedagogy in their setting.

However, individual teachers appeared to regard talk with a colleague – the very opportunity they were missing – as even more significant, since 69% of their comments related to talk.

- Level of impact: sharing new knowledge: dissemination of new knowledge and practice

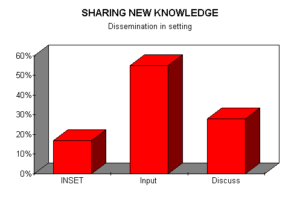

Figure 1 shows that the different ways in which teachers shared their experiences and new knowledge.

Figure 1.

* ‘INSET’ – teachers led an entire INSET session

‘Input’ refers to teachers’ input to staff meeting

‘Discuss’ – talked informally with some colleagues

“I recently gave an in-house INSET to the teaching staff at school. I decided to use Powerpoint. I began with a brief up-date on e-learning and related it to the recent consultation document produced by the government in July this year” (Sarah, Wigan).

Significantly teachers who had led INSET or contributed to a staff meeting also discussed aspects of the project with their immediate colleagues. Furthermore some had discussions with other staff in their setting; with visitors (including student teachers and supply teachers) and with staff in other Early Years settings. This is noteworthy since one of the key requirements of Early Excellence Centres is to ‘disseminate good practice’.

- Level of impact: impact on colleagues’ understanding and practice

50% of the teachers felt that the project had had some impact on colleagues’ practice: between them they listed 17 different indicators of change. Examples include:

“Some staff doing NVQ training – it helped their understanding”

“SENCO interested”

“Staff in local day nursery more aware”

“Staff have been collating samples of children’s work”

Discussion

My aim has been to evaluate teachers’ collaboration in an online community and its impact on classroom practice. A noteworthy aspect of the study has been the identification of ways in which discussion supported shared meaning.

Aim 1: the significance of context and language in constructing learners’ understanding

The significance of Bakhtin’s ventriloquation within the discussion forum cannot be underestimated. Furthermore, teachers’ high level of emphasis on metacognition (whilst probably unconscious) indicates a concern with learning about learning. One of the features of this study was the powerful context providing by both text (talk) and the visual examples: embedding teachers’ e-graphics may be one factor in contributing to successful outcomes. This feature has the potential to be used in educational contexts across all subjects and all phases. Laurillard (2002) argues that ‘educational technologies, especially new ones, demand effort and ingenuity in the development of materials, but rarely is this extended to the embedding of these materials in their education niche’ (cited in Shephard, Riddy, Warren and Mathias, 2003, p.246).

“It’s great to share ideas and especially to get feedback from the graphics I put on. Gave me new ways of looking at their work” (Louise, Greenwich).

Aim 2: the impact of involvement in collaborative discussion, on classroom practice

Collaboration

Collaboration led to positive outcomes in terms of developing shared meaning through language. More specifically participating with a colleague (pair) provided many benefits. Candy proposes that ‘for successful partnerships, a longer-term relationship, in which trust and confidence can be built up has real advantages’ (Candy, 1997, p.15). The value of pair work is exemplified by Holmes who concluded that students performed ‘substantially better when they worked in pairs’ (2003, p.256).

Wenger outlines essential features of a community of practice that combine ‘joint enterprise, mutuality (and) developing a shared repertoire’ (Wenger, 2000, p.229). As teachers discussed their practice and described children’s learning, relevant ‘stories’ they told supported their apprenticeship, through which ‘dealing with past problems is a way of thinking together’ (Mercer, 2000, p. 111). Stories appear to play a major role in decision making (Jordan, 1989) with personal story telling offering ‘tool of diagnosis and reinterpretation’ (Lave & Wenger, 1991, p. 109). However, Barnett, (1997) warns that teachers need to practice critical skills and go beyond ‘uncritical storytelling’ (cited in Preston, 2003, p. 14).

Through collaborative participation, teachers moved between discussions exploring (informal) theory building and pedagogy in synergy. Drawing on Levi-Strauss’s bricolage (1966), Papert argues that ‘in the most fundamental sense, we, as learners are all bricoleurs’ (1993, p. 173): this signifies that we are continually ‘moving ideas from the concrete to the abstract and back again’ (Dillon, 2003. p.1). The online socialization that Salmon so clearly outlines (2002) is recognised as significant in creating a sense of ‘community’ in which learners move from ‘peripheral participation’ toward ‘full participation in the socio-cultural practices of a community’ (Lave & Wenger, 1991, p. 29) and one in which the importance of the community’s ecology is recognised (Nardi & Day, 1999).

Aim 3: the extent to which e-learning provides an effective means of professional development

My concern about the level of impact of traditional (face-to-face) CPD is shared by Feist who observes that CPD initiatives ‘have been criticized for their failure to produce significant changes in either teaching practice or student learning’ (2003, p.1). She proposes that successful e-learning is achieved through learner-centred learning (Cuban 2001; Ertmer; 1999; also Rogers, 1983).

A recent review of 17 research studies into collaborative CPD (not online) found ‘that sustained and collaborative CPD was linked to a positive impact on teachers’ classroom practice’ (Rundell & Seddon, 2003. p. 3). The review found that teachers’ shared a stronger belief in self-efficacy and reported a high level of commitment to change. Their enthusiasm for collaborative working and professional learning had increased. Furthermore, the recognition that peer support was beneficial featured strongly in many of the studies.

Sorenson and Takle (2002) argue that ‘knowledge building dialogue within the context of collaborative learning appears to be a complex challenge’ (p.30); this may be in part due to the nature of a virtual environment (Scardamalia & Berieter, 1996). In this study teachers’ subject and pedagogical learning developed significantly, with an element of enjoyment and challenge:

“When you’ve been teaching for some years, most courses offer nothing new – they say the same thing, or they say the same thing in a different way. It’s a very long time for me since something like this has come along. The difference with this (research) project is that it was an intellectual challenge.”

(Jan, Camden).

Involvement led to impact on teachers’ classroom practice that in many instances occurred earlier in the project that expected and extended beyond what we had hoped, involving other (non-project) colleagues and staff outside of their settings. None of the project teachers had previously explored the theory or practice of the content of discussions (only very recently published). However, teachers’ comments during early weeks of the project indicated that they were able to relate what they were learning online to children’s work and gradually explore the pedagogy to support this: in other words, to move as bricoleurs between emerging theories and their developing practice.

It is worth considering whether we are seeing a revolutionary means of learning that will ultimately replace pedagogy with andragogy. Connor argues that in moving towards such a model, ‘in the information age, the implications of a move from teacher-centred to learner centred education are staggering’ (1997-2003, p. 2).

Forward to the future

‘The challenge of educating for the 21st century in contrast to “industrial era” education,’ Roo argues ‘is to find the best ways in which students can master a broader range of knowledge, make decisions given incomplete information and uncertain goals, manage team work and filter information rather than simply find it’ (1999, p. 2). He argues that e-learning has the potential ‘to bring the white heat of the technological revolution to education in a way that the field of educational technology has long aimed for’. Nonetheless, Nardi and O’Day emphasise the need to create a healthy ‘information ecology (which) takes time to grow, just as rain forests and coral reefs do’ (1999. p 58). Since the project ended (July 2003) a number of the project teachers have asked that we continue the forum in 2004, thereby acting as a further indicator of success. In this we wish to move the level of discussion into ‘exploratory’ talk (Wegerif, 2003) and invite teachers to focus on their own practice-based research projects. It is not technology alone that can drive CPD through e-learning forward, but technology used sensitively by e-facilitators to create innovative environments for learning.

There is no doubt that the lived experience of an e-facilitator is very different to that of a leader of traditional (face-to-face) professional development. Heilbron emphasises that the role of the teacher is changing: ‘she will become a facilitator of access to information, as opposed to the guardian of bodies of knowledge to be acquired’ (2000, p. 7). But it is to be hoped that e-learners will themselves generate new theories and emergent paradigms that can be ‘mined’ by others later. This will lead to a blurring of the division between CPD providers (e-facilitators) and participants, and has the potential to create shared cognition (Brown Collins & Duguid, 1988; Lave & Wenger, 1991). Such a new paradigm will not, Flood believes, ‘be one based on learning, but one based on the development of environments that facilitate learning’ (Flood, no date. p. 2).

For the participants in these virtual communities of practice, this study has demonstrated that there are often unexpected gains and deep levels of learning which in turn are carried forward to the children in the teachers’ own settings and classes.

It is hoped that this study will make a small contribution to the rapidly growing body of evidence-based research on e-learning and education and point some ways forward to the future.

[divide margin_top=”10″ margin_bottom=”10″ color=”#a0a0a0″]References & Contacts

None available

[divide margin_top=”10″ margin_bottom=”10″ color=”#a0a0a0″] [review] [/s2If]